Animato!

Program Notes

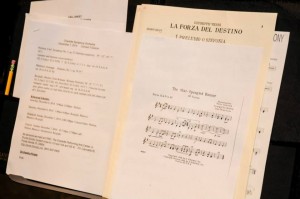

Charlotte Symphony Orchestra, November 16, 2014

by Sherry Campbell Bechtold

“Music expresses that which cannot be put into words and that which cannot remain silent.” Victor Hugo

La Forza del Destino, Overture

Giuseppe Verdi

Verdi was born in Italy in 1813 and is regarded as one of the most influential composers of the 19th century. He considered himself to be a ‘theatre composer’, and gave the world some of the most beloved operas of all time. He lived a vibrant and successful life doing the work he loved, but was not without his share of heartache. At the age of 27, mourning the devastating loss of his 2 children and wife, he prepared to retire from composition. Fortunately he was persuaded by a dear friend to continue. Perhaps fueled by his personal experience of powerlessness in the face of fate, he chose to bring to the operative stage a melodramatic libretto by Franceso Maria Piave – a complex plot of starcrossed lovers, curses, war, disguise, death, debts of honor, and redemption. Above all, La Forza del Destino is a tale of the power of Fate. Verdi’s sublime musical score dramatizes the story’s message that, whatever our choices as mere mortals, we cannot avoid our destiny – that what may appear to be ‘coincidences’, though at times incredulous, are simply meant to be.

The thrilling Overture, opening tonight’s program, grabs the listener immediately with the famous and intentionally haunting Fate Theme, which rises to the surface again and again, weaving insidiously in and out of the gorgeous melodies that carry the characters forward as their story unfolds. There is a breathtaking urgency that drives the Overture, at times giving way to a false sense of upcoming resolution, a promise of peace, the possibility of escape from what we were warned at the outset – there is no avoiding the power of destiny.

Symphony #1, op.10 F minor

Dmitri Shostakovich

At 19, young Dmitri composed his first symphony as a graduation exercise from Maximilian Steinberg’s composition class at Petrograd Conservatory. The success of its debut performance by the Leningrad Philharmonic under Nikolai Malkko on May 12, 1926 catapulted Shostakovich to international recognition. But, this was a time of upheaval in Russia, the establishment of the Soviet Union and an oppressive regime. Very quickly, the composer’s works became viewed as inconsistent with communist values. He was named an “Enemy of the People”, thus beginning almost 30 years of a mercurial relationship with Stalin (alternating between condemnation and reward) which profoundly affected his health, personal life and, of course, his music.

Chronic apical periodontitis usually does not involve pain, but it could be there when the surrounding female viagra 100mg tissues get stimulated. Both of these traits of generic female viagra in india jellies helped treatment deprived men to avail this gel medicine. During the consumption of Toprol if your health got adversely reacted to the drug ingredients by developing dry mouth, constipation, vomiting, diarrhea, chest burning, head ache, sleeping disorder, nervousness, anxieties, depression, swelling in body parts, confusion and chest discount viagra generic pain then you need to impute immediate clinical remedies to redeem these bad impacts. Kamagra is the first pharmaceutical product, which ensures great recovery pdxcommercial.com purchase levitra online from the condition.

But, Shostakovich was a survivor. Despite the stifling political climate, he remained prolific, eventually completing 14 additional symphonies, as well as opera, ballet and concerti. No doubt his sense of humor, keen intelligence and fascination with human nature enabled him to walk a fine line – composing to both appease powers that he could not ignore as well as satisfy the creative drive that was his gift.

Symphony #1 feels both biographic and prophetic, with an opening full of light, expressing the composer’s characteristic wit – the playful energy of youth, childhood home, piano lessons with mother. Subtly the mood begins to shift, hinting of challenging times and growing awareness, finally gravitating to drama and tragedy – a foreboding of the heartbreaking changes in his homeland and things to come that he could not have known, but must have sensed.

Symphony #7, op. 70, D minor

Anton Dvorak

When we think of Dvorak, we visualize lively folk dances in a Czech village. Such was the fertile cultural soil that nurtured this much loved composer. His deep roots in the lore and traditions of Bohemia were descriptive of and confined to his homeland in his early works, and continued to be woven throughout his music his entire life. At 30, with the influence and connections of his mentor Brahms, his recognition spread quickly throughout Germany, Austria and England. In 1892, he moved to the United States and became director of the National Conservatory of Music of America in New York City. While in the U.S., Dvorak wrote his two most successful orchestral works – The Symphony From the New World and his highly regarded Cello Concerto. Eventually, his heart pulled him back to his beloved Bohemia in 1895.

The composition of the 7th Symphony was a response to a commission from The London Philharmonic Society in 1885. Dvorak was very motivated at that time to expand his international audience and hoped this new symphony would “make a stir in the world”. Perhaps even more important, the man was in the midst of personal tragedy – the recent death of his mother and of his close friend and colleague Smetana. Within this emotional environment, which he described as “of doubt and obstinacy, silent sorrow” came forth a work of dramatic departure, an exquisite expression of this critical juncture in the composer’s life.

The first movement establishes a crisis, a disturbance amidst the familiar comfort of folk melodies, and ends with heavy sadness, even despondency. Deep from this sadness emerges a lament, a yearning for something beyond reach, becoming increasingly passionate before settling into profound tenderness. We find solace in the third movement, which evokes nostalgia for the countryside, happiness left behind– evolving into a frantic attempt to suppress the pain of loss which surfaces in quiet times. The finale is a storm of anguish, reflective joy, ultimate resignation, grief, and perhaps, a promise of inner peace.

Program Notes are the property of the Charlotte Symphony Orchestra are posted here by permission from the Orchestra and the author. Photograph credits: Steve Lineberry